It seems to be a good year for Orchis militaris – the meadows in biking distance from Frankfurt are full with violet inflorescences. And this time, in the fifth year of continous observation, there is a second albiflora form of an Orchis militaris, just ten meters away from the place of the first plant. It has a height of 20 cm, a rosette of three leaves and about ten flowers. The reproduction of albiflora forms is difficult, since the DNA sequence responsible for the lack of flower pigments is recessive, but here it has obviously happened. The first albiflora plant is about 30 cm tall, with five foliage leaves and about 25 flowers:

Nigritella bicolor – a new, but well known species

A new species description offers the chance to clarify open questions while studying the alpine Nigritella flora: In the latest edition of the Journal of European Orchids (1/2010), Wolfram Foelsche describes a broad spectrum of doubtful cases where Nigritella plants have been identified as Nigritella rubra without showing the characteristics of this plant as it was described by Richard Wettstein in 1889. With Nigritella rubra sepals and petals should have about the same width. But many plants identified as Nigritella rubra have petals which are considerably slimmer than the sepals. Additionally there are also differences regarding the form of the lip and the colour of the inflorescence: In most cases the plant now described as Nigritella bicolor shows a brighter red in the lower part of the inflorescence than in its upper part. And Nigritella bicolor has a longer spur than Nigritella rubra.

“With its striking inflorescence – above a rim with brightly shining rays the rows of rose-coloured flowers are displayed while the tips of bracts are set apart in dark-red – this new species, without doubt, is our splendid, most attractive nigritella”, Foelsche writes. According to his studies the majority of the photos used to illustrate Nigritella rubra are actually showing Nigritella bicolor which has a much larger area of distribution. Foelsche notes that the bicolour characteristics may be more or less strongly developed. It’s not possible to confound Nigritella bicolor with colour varieties of Nigritella rhellicani with its open labellum:

Where have all the flowers gone…

Last year, about 800 Anacamptis morio have been flowering in the Rheingau region, west of Wiesbaden – among them five with white flowers. This year, only ten plants are flowering, a decrease of 99 percent. And there wasn’t any Anacamptis morio f. albifora on the meadow. Hiking around the neighboring woods I met a huntsmen who was sawing logs. He told me that wild hogs are probably the cause why the orchids have been diminished to such a great extent. The long lasting winter has done its part to prompt the hogs searching for orchid roots. On the adjacent meadow I’ve found about 20 Orchis mascula in the beginning of flowering.

Ophrys bertolonii “albiflora”

With its deeply pink to purple colours in the sepals and petals and a deeply brown labellum, Ophrys bertolonii is one of the most intensely coloured Ophrys species. In Croatia, at the southern tip of Istria, Pavel Heger found a colour variety of Ophrys bertolonii – with an overall green appearance due to the remaining chlorophyll pigments. There are two characteristics which allow to address these plants as an “albiflora” form: 1) The typical marking at the lower end of the labellum is quite white. 2) The hairs at the edges of the labellum are white as well.

This rare plant demonstrates that “albiflora” forms of Ophrys species tend to retain chlorophyll – in contrast to the white flowering forms of Orchis or Anacamptis species. And there are distinct areas of the flower where chlorophyll is not retained as it is the case with the labellum marking of Ophrys bertolonii. Maybe these plants tend to be “white” in order to achieve a certain biological “albiflora” function – but the chlorophyll performance of the flower is still important and thus kept. Special thanks to Pavel for contributing to albiflora.eu!

Rare albiflora form of Orchis spitzelii

In OrchideenJournal 3/2009, Josefa and Richard Thoma describe how they have found two white flowering plants of Orchis spitzelii for the first time in a region they have been visiting for about 20 years. This location in the Alps near Salzburg is the only place where Orchis spitzelii can be found in Austria.

In June 2009, the couple counted 17 plants when Josefa was surprised to find two white flowering Orchis spitzelii. “I didn’t trust my ears”, writes Richard Thoma describing his feelings when his wife exclaimed: “Two whites!” The author named the rare color variation “Orchis spitzelii f. albovirida” – with regard to the green perigone containing chlorophyll pigments.

“Why now, of all times?”, Thoma asks and is looking forward to next year when the want to see if the white forms appear again.

Maybe it’s more than just a “freak of nature” as Thoma is assuming. More substantial research is needed to see if there is a certain function which could explain why certain orchid species develop albiflora forms. Special thanks to Richard Thoma for contributing his photos of the white flowering Orchis spitzelii to albiflora.eu.

not only orchids…

… develop white flowers while their species is supposed to have coloured flowers. This Gentiana germanica, found at Seiser Alm in the Dolomite Alps, is an example.

The plant at the right side has flowers without pigments (anthocyanins). It may be viewed as “Gentiana germanica albiflora”, as Ferdinand Schur has noted in his article “Beitraege zur Flora von Wien” (Oesterreichische Botanische Zeitschrift vol. 11/1860). The correct name should be Gentiana germanica f. albiflora.

Another example found this year in the Swiss region of Aargau is Ajuga reptans f. albiflora which has acquired some horticultural importance.

But neither the Gentianaceae nor the Labiatae (the family of the genus Ajuga) could be viewed as a family with a certain tendency towards developing white flowers – as it is the case with orchids. Maybe another family with an albiflora disposition are the Cactaceae. A charming web gallery of albiflora cacti has been set up by Gerd Weiss presenting more than 50 species.

Orchids of the Rhoen region in Germany

A new publication presents a showcase of all the orchids to be found in the Rhoen Region of central Germany. In this book, the author and photographer Marco Klueber presents a summary of his research in this hilly region. He explains how geological and geographical conditions formed different habitats as there are several types of forests, grassland and marsh areas.

A new publication presents a showcase of all the orchids to be found in the Rhoen Region of central Germany. In this book, the author and photographer Marco Klueber presents a summary of his research in this hilly region. He explains how geological and geographical conditions formed different habitats as there are several types of forests, grassland and marsh areas.

There are 48 different species of orchids growing in this region or confirmed to have been grown there in past times. There are five species which can’t be found today in the Rhoen. Their presentation is a memorial and at the same time a challenge to do everything to preserve these treasures of nature. And Klueber’s publication is an important contribution to such efforts. Only public awareness offers the basis for the necessary political decisions to protect those regions.

In addition to the presentation of the region there is an introduction to the family of orchids and its biological specialties. The main part of the book are in-depth profiles of all species with great photos. The author also presents several albiflora varieties such as Dactylorhiza fuchsii, Orchis purpurea or Cephalanthera rubra. Marco Klueber has also made important contributions to this web site. At the end the book presents six proposals for hiking tours where you can find orchids. (Marco Klueber: Orchideen in der Rhoen. Kuenzell-Dietershausen, edition alpha 2009. 256 pages. 23.90 Euro)

Colour change more common among diploid Dactylorhiza

In an e-mail exchange following his recent article in the Journal Europaeischer Orchideen (JEO), Richard Bateman, orchid specialist at Kew Gardens, wrote me that albiflora plants “are far more common among diploid Dactylorhiza species than tetraploid species”. A possible reason might be the “buffering of mutations by having four comparable genes in the tetraploid chromosomes”. Diploid species (with 40 chromosomes) are Dactylorhiza fuchsii, D. incarnata and D. sambucina. Tetraploid species (with 80 chromosomes) are D. majalis, D. praetermissa, D. maculata, D. elata, D. sphagnicola and D. traunsteineri.

Albiflora plants of Dactylorhiza fuchsii are quite often observed, and in Ireland there is also the intriguing D. fuchsii ssp. okellyi which is diploid as well. D. incarnata and D. sambucina are known for their colour dimorphism: red and yellow with D. sambucina, purple and yellowish-white with D. incarnata and its var. ochroleuca. In a recent article in the Annals of Botany (2009), Mikael Hedrén and Sofie Nordstroem presented the results of their reasearch about the colour dimorphism with D. incarnata. They observed that there was “no clear pattern of habitat differentiation … among the colour morphs”. With D. incarnata var. ochroleuca “the lack of anthocyanins is probably due to a particular recessive allele in homozygous form” – the diploid chromosome set has both alleles determining the lack of purple in the flowers.

Besides genetics, colour also affects the pollination function of orchid flowers. Bateman wrote me that “in at least a few cases, instantaneous loss of anthocyanins (or even just radical decrease in anthocyanin production) must affect pollinator preference, and lead to lineage divergence”. A potential example of such an evolutionary process could be Gymnadenia frivaldii as a relative of Gymnadenia conopsea.

But in general the question of a certain functionality of colour change is still unanswered. Following his mentioning of white flowers in the above mentioned JEO article, Bateman wrote me it would be “more correct to use the term ‘parallelism’ rather than ‘convergence’, since in most cases no-one has demonstrated a change of function or ‘behaviour’ in the abnormal white flowers”. He further noted “the probability that many different mutations and epimutations generate white flowers”. Recognising that there are quite many open questions, Bateman also asked “whether white is actually a colour at all”, pointing to the “very simple shifts between ‘white’ flowers and ‘green’ flowers in Platanthera”.

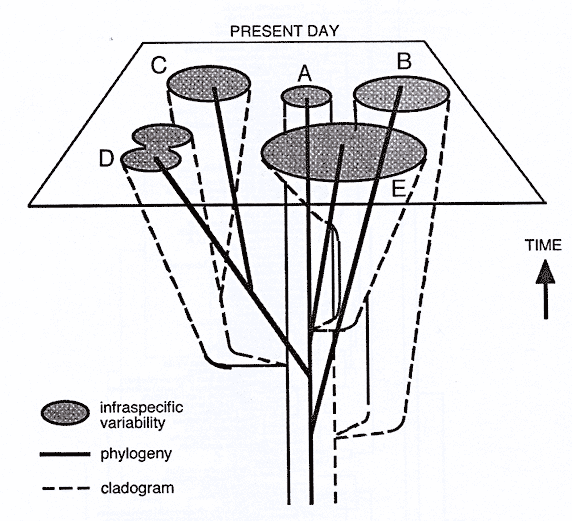

White flowers as a result of convergent evolution

In an essay about the taxonomic mess with European orchids, Richard Bateman stresses the importance to develop clear criteria for classification instead of individualistic conclusions. The article titled “Evolutionary classification of maximising explicit evidence and minimising authoritarian speculation” (In: Journal Europäischer Orchideen, Vol. 41/2, July 2009) explains how a monophyletic classification (i.e. a classification with a group of organisms forming a clade with a common ancestor and comprising all the descendants of this ancestor) can be derived from the phylogeny (evolution) of species.

Bateman recognises the value of morphological characteristics, but stresses that molecular data should be the main source for a scientific taxonomy. He criticizes that other classifications are often only “the result of personal opinion” and says: “21st Century data are being constrained by voluntarily retaining an 18th Century approach to biological classification”. Regarding taxonomic debates about the genera Dactylorhiza/Coeloglossum, Neottia/Listera or Gymnadenia/Nigritella he complains: “Authors decide which names they will accept and which they will reject from the many classifications already available, as though they were selecting products from the supermarket shelves.”

Arguing for clear rules founded on molecular research, Bateman also mentions the “origination of white-flowered individuals in many orchid lineages” as a result of a convergent evolution – this term describes the development of similar features with species who have no genetic relationship, often initiated by functional or environmental adaptation. But is there really such an adaptation when orchids develop white flowers, “achieved by suppressing any one stage in the biosynthetic pathway that generates anthocyanin pigments”? And what would be the object of such an adaptation?

Exhibition in Frankfurt demonstrates color in nature

“The palette of colors in nature is almost infinite”, says the botanist Hilke Steinecke of the Palmengarten in Frankfurt. There, this palette is displayed in an exhibition which can be visited until November 1st. The exhibition also explains the role of pigments in the colors of flowers and how fertilizing insects see colors.

“The palette of colors in nature is almost infinite”, says the botanist Hilke Steinecke of the Palmengarten in Frankfurt. There, this palette is displayed in an exhibition which can be visited until November 1st. The exhibition also explains the role of pigments in the colors of flowers and how fertilizing insects see colors.

An interesting demonstration shows the acid sensitivity of anthocyanins. When a drip of vinegar is placed on the violet flower of Ipomoea, its color changes to pink. “In an acid milieu many anthocyanins are rose-pink, in an alkaline milieu blue”, as it is stated in the catalogue. This phenomenon could also explain the color variations of Nigritella nigra ssp. rhellicani in the Dolomite Alps – these occur especially in a region with rather acid soil.