Following the benchmark books about the genera Anacamptis, Neotinea and Orchis (together with Horst Kretzschmar und Helga Dietrich, 2007) as well as a monograph about the genus Cypripedium (2009), Wolfgang Eccarius now has finished his long lasting work and has published a compendium about the Dactylorhiza orchids.

The book closes a big gap and covers a genus of orchids which is especially rich in species and quite widespread in Europe. As he has established in former publications, the author at first gives a comprehensive introduction before portraying 37 species and 46 subspecies. Eccarius explains his methodological approach and offers a summary of the research history, beginning with the plant book of Otto Brunfels published in 1534. The book abstains from giving a system to identify the species by morphological indicators. But a tree of the genus structure based on genetical research offers a good overview about the manifold Dactylorhiza orchids and their relations.

In his description, Eccarius has taken some main decisions. He abstains from describing varieties and forms, arguing that those terms are “highly problematic” with Dactylorhiza. “The main goal of the author was a genus structure wich matches logical principles as well as the needs of observations in the field.” He stresses that’s it’s more important to differentiate between the ten sections than defining species: “With Dactylorhiza, sections are much easier to define than species.” For example, the Fuchsiae form a section of their own, together with Dactylorhiza saccifera. The section of Majales comprise Dactylorhiza majalis, Dactylorhiza cordigera and Dactylorhiza elata.

It’s comprehensible that Eccarius views Coeloglossum viride as Dactylorhiza viridis. The Viridae are presented as a subgenus, in addition to the subgenus Dactylorhiza. Other taxonomic decisions are more thought provoking. For example when the yellowish Early Marsh Orchid no longer is a subspecies of Dactylorhiza incarnata, but an own species Dactylorhiza ochroleuca – because there are only very few hybrids between both “which justifies the treatment as a single species in the view of the author”.

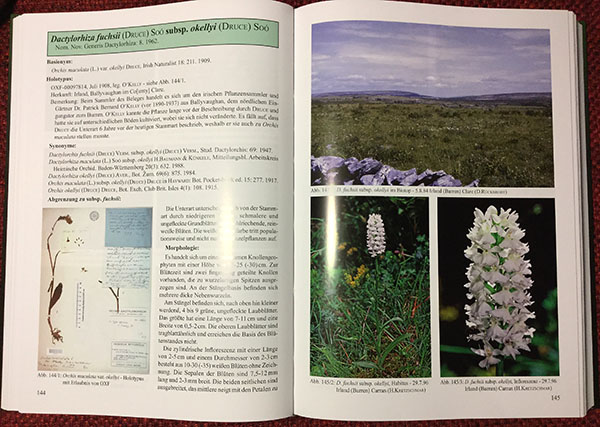

Difficult are the explanations about the white flowering Dactylorhiza fuchsii in Ireland, which are elevated by Eccarius to the status of a subspecies – while most experts view the okelly taxon of Dactylorhiza fuchsii as a variety. And the morphological description of the author is not quite helpful in the field: “The subspecies is different by its lower growth” – while the photos show rather high plants. And: “The white color of flowers is shown by whole populations and not only by single plants.”

But this is also valid for Dactylorhiza majalis subsp. calcifugiens, which is presented by Eccarius only as a synonym to Dactylorhiza sphagnicola. The book shows a photo of a plant from the German region of Celle which seems to be an albiflora form of Dactylorhiza sphagnicola, but which is quite different form the calcifugiens population in Northern Denmark.

Quite useful are the explanations about Dactylorhiza maculata, which is presented as a west and northern European species, distributed also in Northern Africa and Northern Asia. The color of flower is described as especially variable, from pure white to a soft and light purple.

Eccarius understands the tendency to a color dimorphism (or polymorphism) which is typical for the genus as functionally relevant. With Dactylorhiza romana, sambucina or incarnata this phenomenon serves as a factor, “to avoid quick learning experiences of polinating insects”. This matches with the regionally different tendency of Dactylorhiza fuchsii to develop albiflora forms.

The new book makes big progress in understanding the Dactylorhiza orchids. But for a full perception there is still a lot of research necessary.