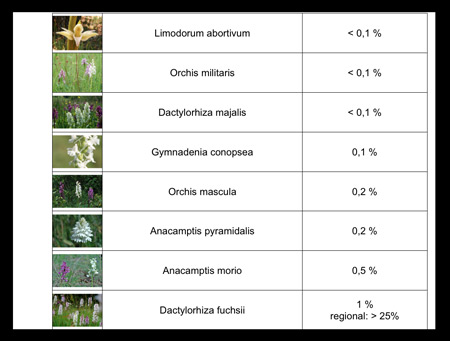

Stets auf der Suche nach Hinweisen zur Erhellung des Albiflora-Phänomens habe ich Richard Bateman in London besucht. Die weiß blühenden Formen „sind für mich von größtem Interesse wegen der unterschiedlichen Häufigkeiten bei den diploiden und tetraploiden Gruppen von Dactylorhiza“, sagte er mir. „Wenn man über die einzelnen diploiden Arten nachdenkt – incarnata, fuchsii, sambucina – so weisen sie allesamt ausgeprägte Farbvarietäten auf. Und sie haben alle eine gewisse Anzahl von sehr weißen oder blassen Individuen.“ Ganz anders aber sind die Beobachtungen bei den tetraploiden Dactylorhiza-Arten wie praetermissa, majalis oder alpestris. Bateman sagte: „In 30 Jahren der Beobachtungen im Feld habe ich nur eine weiß blühende praetermissa und eine weiße Form von traunsteinerioides gesehen.“ Um einiges jünger ist das Projekt albiflora.eu – aber bisher gingen hier nur Berichte über ein paar verstreute Beobachtungen von weiß blühenden Dactylorhiza majalis ein – und keine von praetermissa oder traunsteineri. Als eine mögliche Erklärung merkte Bateman an: „Wahrscheinlich ist bei den Tetraploiden ein Minimum von vier Kopien eines Gens mit einer Fehlfunktion erforderlich, um Albinismus zu verursachen. Daher denke ich, dass die Tetraploiden einen Puffer gegen Albinismus besitzen, indem sie über zusätzliche Kopien der Gene verfügen, welche die Anthocyanin-Pigmente erzeugen.“

Auf das Argument der negativen Konnotation des Begriffs Fehlfunktion antwortete Bateman: „Die meisten Organismen sind so ‚entworfen‘, dass sie so bleiben, wie sie sind und sich nicht [grundlegend] ändern. Daher ist aus genetischer Perspektive jede zum Vorschein kommende Änderung eine Fehlfunktion. Ich stimme zu, dass eine Fehlfunktion auch ehger nützlich als negativ sein kann, aber meistens ist es negativ.“

Batemans vorrangige Forschungsinteressen sind die Fragen der Artenbildung oder zumindest die Frage, was zu evolutionären Abweichungen zwischen Populationen führen könnte: „Die Ebene der Gattungen ist – für mich zumindest – geklärt. Nun interessiert mich die Artenebene am meisten. Hier gibt es noch die größten Herausforderungen – wie die Artenbildung bei Orchideen verläuft.“ Trotz einer gewaltigen Fachliteratur zu diesem Thema seien diese Fragen, so sagt Bateman, immer noch nicht angemessen beantwortet. „Jedes Mal, wenn ich eine bestimmte Gruppe von Orchideen untersuche, fällt die Antwort [auf diese Frage] unterschiedlich aus.“ So ist bislang keine Verallgemeinerung möglich. Allerdings merkt Bateman an: „Ich bin der festen Überzeugung, dass die Bedeutung [spezifischer] Bestäuber von vielen Forschern übertrieben wird.“

Zumindest eine allgemeine Beobachtung scheint sicher zu sein, wie Bateman anmerkt: „Es werden ständig neue [evolutionäre] Strategien ausprobiert – mehr als die meisten Leute glauben – aber ich denke, sie sind weniger oft erfolgreich, als die meisten Leute annehmen.“

Neben derartigen Betrachtungen über Stabilität und Wandel in der Genetik von Orchideen fragten wir uns, warum hypochrome Formen von Ophrys eher grün als weiß sind – offensichtlich enthalten die Ophrys-Blüten immer noch ChlorophylI, selbst wenn die Anthocyanine fehlen – und das aus gutem Grund: „Die Blattrosetten von Ophrys (und auch von Himantoglossum) neigen zum Verblühen, bevor die Blüten sich richtig öffnen“, sagte Bateman. „Ich denke nicht, dass eine umfangreiche Versorgung mit Nährstoffen [zwischen Wurzel und Blüte] stattfindet. Die Blüte ist autonom geworden … während die Blüten bei Orchis oder Anacamptis weit weniger unabhängig sind.“ Ophrys-Blüten sind also ziemlich einzigartig. „Wenn man an den Blüten arbeitet, sie aufschneidet und unter dem Mikroskop betrachtet, ist es verblüffend zu sehen, wie viel Energie in eine Ophrys-Blüte investiert ist. Da gibt es sehr viel Gewebe.“

Nach dem Besuch waren dann die Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew der richtige Ort, um weiter über die Wunder der Natur zu sinnieren. (Mit Dank an Richard Bateman für die Überprüfung der Zitate, zusätzliche Anmerkungen sind mit eckigen Klammern kenntlich gemacht)